Curated and written by Koulla Xinisteris

Bronwyn Lace’s Response, an exhibition in dialogue with Neels Coetzee’s Crucible, opens at Circa on 1 October 2015. Elements of Coetzee’s exhibition will remain in the gallery space, setting up a contrapuntal dynamic between the works of the two artists. Along with the enlarged skulls of Measure (2015), which were exhibited for the first time as part of Crucible, Response is a posthumous meditation. The staging of Lace’s response to Coetzee’s work in the same venue at almost the same time is informed by a curatorial desire to explore and transcend the limits of a single autonomous oeuvre by manifesting the intentions of an artist beyond his own lifetime and choreographing a visual conversation between two artists.

Lace’s connection to Coetzee’s life and work runs deep. Although she was never taught by him, she came to know him well in the final years of his life and was present at the time of his death. Death is not unfamiliar to Lace. As the daughter of a hospice nurse, the last stages of strangers’ lives are familiar to her. Nonetheless, Coetzee’s death was her first close and personal loss. As a friend and fellow artist, she took part in the Greek rituals that were carried out to mark his passing, witnessing his last breath, and the intimacy and tenderness with which he left the world.

The idea of a visual dialogue between two sculptors arose out of an abiding sense of congruity in the spatial and thematic interests of the two artists, and was distilled in many hours of conversation with Lace. And some of the inspiration for this project comes from Lace’s early-career interest in Coetzee’s work, which she first encountered at the Durban Art Gallery in early 2006 before she met him and came to know him and his work more closely.

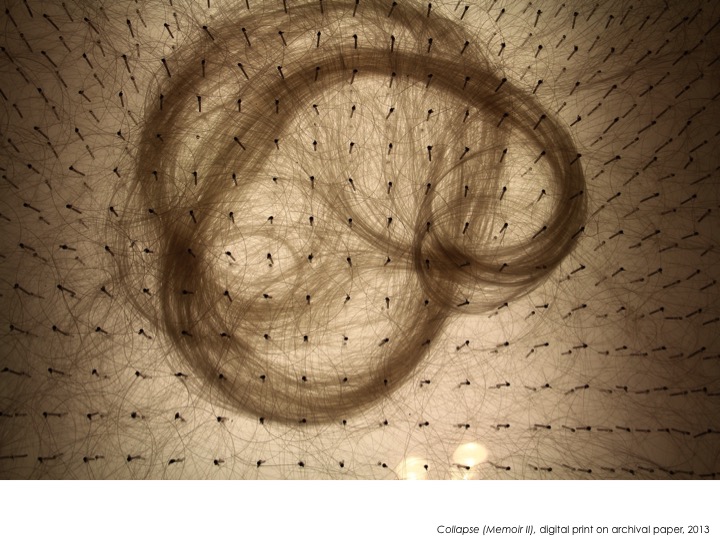

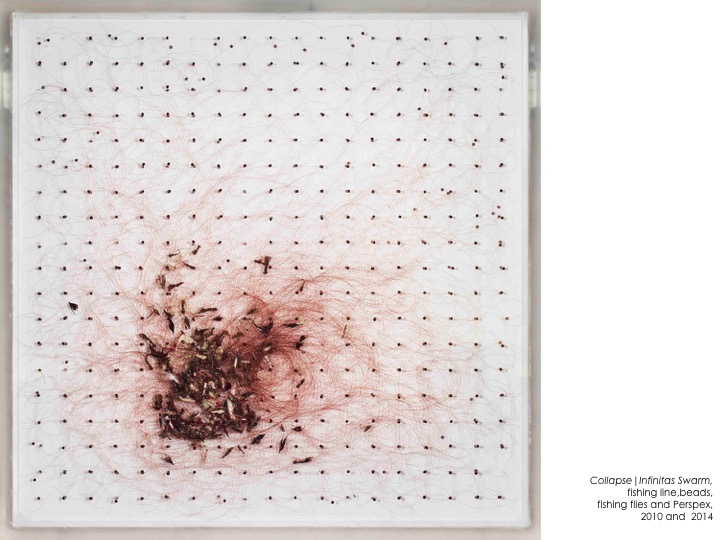

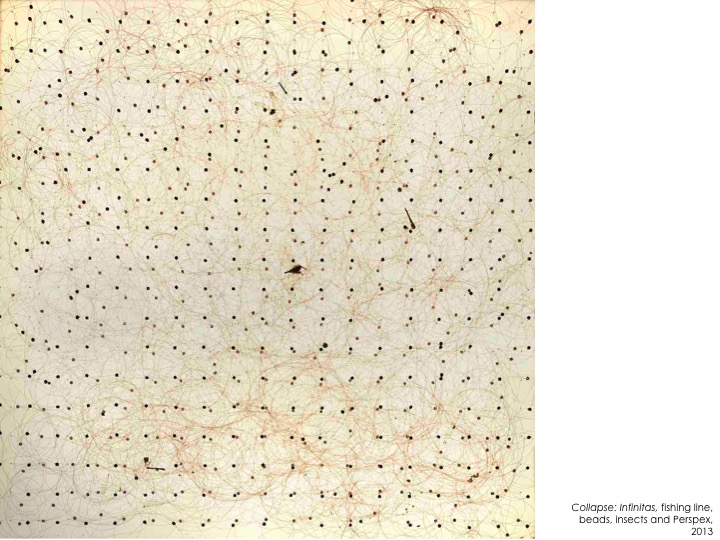

Lace’s early installation works reveal her abiding interest, since her student days, in the fragile and numinous. Writing in response to Teeming, her exhibition held at Speke Photographic in 2014, I observed that:

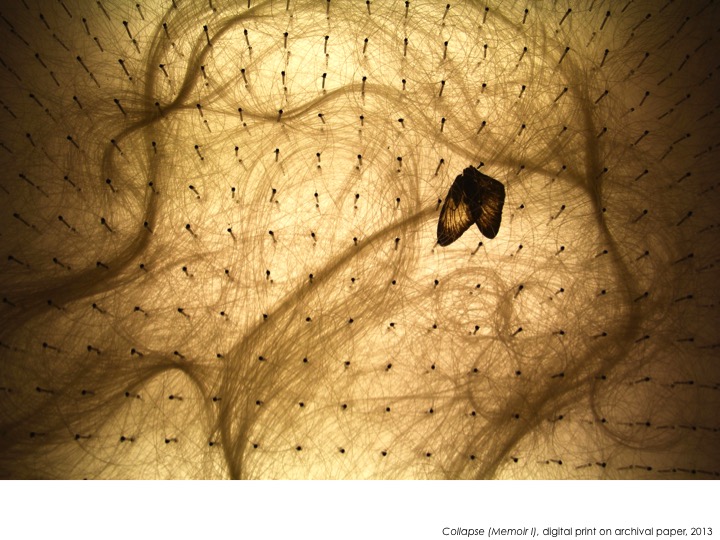

Lace transforms and uses the darker elements of life – like death and decay, abandon and neglect – as ingredients to foster in-between spaces or platforms portraying fragility and vulnerability. She uses, for her reference, raw material from the world of nature, bits of species, gut, light, insects, shark eggs, but equally bones – bones bled of blood – the remnants of life, the dead, and then tries to resuscitate spirit as a way to a road that leads on… Lace’s work renders the invisible visible, thereby grounding it, however fragile, elusive and mysterious it may be. Some conditions of life, like death, will not and cannot easily be ameliorated by time. Time is what she entangles with her crushed, wounded and dead. Trapped under glue or glass, cocooned in chaotic threads of gut, held immobile in time, and yet suggesting movement out of it, their forms veer toward and conjure light.

Lace’s response to Coetzee’s life and work has taken form within an arena of conversation, curatorial imaginings and past and present observations. In that sense, it has been wrought over many years. Yet this body of work, made leading up to and during the time of Coetzee’s Crucible exhibition, is a live and immediate response to the resurrection of his oeuvre. Lace’s final installation will only take shape after the time of writing.

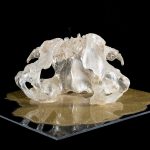

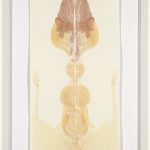

Ascension, which forms part of the Crucible/Response exhibition, was inspired by the memory of Coetzee’s hair being caressed as he was dying. This memory and the notion of spirit intertwine in the interplay of silver gut and light, gesturing toward the idea of transcendence or metamorphosis. A visceral work, it offers a sense of the spirit transcending from this life to another. Lace’s rendition of the moment of transition is redolent with deep spiritual sypatico. Her portrayal of this experience emanates from a focus on the head, which links the work of both artists. For Coetzee, the skull is the locus of transmutation. In Lace’s response, the pelvis is the birthing point for transformation/new possibilities. The pelvis is rendered with light. Its fragility yet steady illumination brings comfort and release.

Both artists are architects or surgeons, dissecting and assembling life. In experiencing these works through our living senses, we are the human dimension.

Productive tensions are set in motion by the juxtaposition of solid and translucent forms. The conscious spatial shapes surrounding the sculptures are charged with presence, prescience, predicament, and shared concerns emanate from the play of tragedy and vitality in the works’ bodily, sensual surfaces.

Lace’s trajectory is imbued with auratic effects – layered light ameliorating traces of disaster and death. The passage of light is central to her personal trajectory. As I observed in 2014:

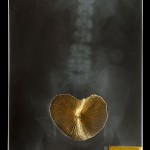

Her work reveals that light is never certain, never stable enough to sufficiently overcome darkness. But her relentless ability to naturally ‘teem’, to want to give birth to, courageously straddles the liminal space between life and death – holding life by a thread if needs be. While she teams gut with corpse, and other fragile materials, she buries the dead and births the luminous. Yet she leaves her materials as vulnerable as the life of a honeybee. Her works suggest that, just as humans have threatened the honeybee, they are a threat, equally dire, to themselves. And so, the images are left ‘bleeding’ and join the world of impermanence and unbounded complexity’… as shown in the silver and gold series on exhibition – because consciousness is the gift that humans neglect.

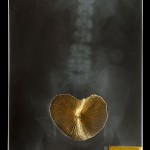

In her two-dimensional x-ray works, the golden thread is the source of light that ameliorates the darkness – in this case the darkness that might lurk within the ailing body.

Experienced in intimate engagement with each other, these works prompt uneasy queries in relation to the nature of life, death and transcendence, giving force to the inconclusive and the unknown. Encountering the layering of light in Lace’s work in relation to Coetzee skulls, figures and shields is an experience of simultaneous unease and comfort. In as much as there is wordly struggle, there is also a mystic quiet, which draws the viewer into its fold.

Lace’s response was forged in relation to Coetzee’s Skull Series. Coetzee’s skulls depict the essence of a life lived with fervent philosophical engagement giving rise to an immanent sense of potential in death – a sense of death providing hope, new beginnings on different levels, open passages.

While he fixed his focus on the skull – the seat of thought and of the contradictions inherent to the the power of mind – Lace gravitates to the pelvis with its own hollowed sockets and mysterious jaws. Stripped of flesh, its difficult passages of entrance and exit are disclosed; places of sensuality and sexuality. There is interplay between the promise of nurturing light and the play of ephemeral shadows and reflections, which render the forms fluid, cold and ghostly at times – antithetical to the solid bronze of Coetzee’s sensual, wracked forms and vital surfaces.

Antithesis is always a certainty – as daunting as the human condition. And these transient and transitional carriers of life culminate in altars for the dead. Both bodies of work are centrally concerned with the theme of transition, giving form to mired and illuminated thresholds. Neither complex nor simple, a merging and union occurs in these artists’ respective journeys of passage and blockage. Both Ascension and Crucible are stripped of flesh, intensifying the material and the void.

In essence and content there are great similarities between the work of Lace and Coetzee. Figures of fragility, firmly poised on the edge of sorrow or hope/faith are common to both artists’ work. Yet the work of each artist has its distinctive tenor. Their materials are markedly dissimilar and their forms resonate with individual iconography. Whereas Coetzee’s works are bronzes, watercolours and drawings, Lace’s repertoire comprises resin, gut, x-rays, silver and gold thread and light.

Lace was particularly captivated by Coetzee’s drawings and spent many hours mulling over and deciphering the work, making connections, looking at the light, seeing the lines. Observing the way in which Coetzee’s ideas would spontaneously drop onto the page engaged her imagination, moving her to further intensify the mysteries of light in her work that are so much her signature.

Lace refers to Coetzee as a postmodernist and a conceptual artist, but also a master draftsman and technician. Her response has also been strongly inspired by the long-lost traditions of skill and foundry work that were such elemental aspects of Coetzee’s dedicated practice.

Lace is both nuanced in her own vision and empathetic to the themes and issues at play in Coetzee’s work. Both bodies of work offer an acute bodily account of the conditions of metaphysical struggle – the danger, fragility, but also intense vitality – and the choice to deal directly with the tragedy of death that resonates so strongly for all humans.

Response Catalogue